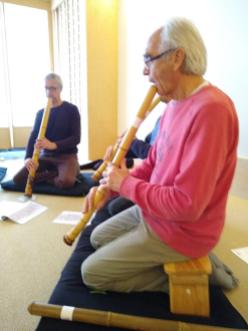

Last Friday, I had the great opportunity to participate to a Kyotaku workshop for beginners, organised by the Dutch Kyotaku player Hans van Loon, who had invited his master Tilopa Burdach.

It was for me the chance to meet the Dutch-Belgium group of Kyotaku players, and of course, Tilo himself!

The Kyotaku is a large bore jinashi shakuhachi “old style” which tradition was revived by Nishimura Koku (1915-2002), who was Tilo’s master. The minimum length starts at 2.2 and goes up to about 3.2. I was very curious to try it and hear it played live.

Tilo brought many flutes, all different in length, origin of bamboo (Japan, Italy, France), weight and bore. After trying half of them, I chose a Japanese 2.7 which fitted very well on my small chin and under my fingers. I love to try different flutes and listen to them. This one revealed quite rapidly its beautiful sound to me. Maybe even more than with the shakuhachi, you absolutely need to release tension. Any unnecessary tension blocks the sound. When you free the sound, it magically flourishes like a beautiful flower.

Blowing softly

It took me some time to discipline myself to always blow softly. I like to try the flute in all its range of dynamics. It doesn’t matter when you play alone, but of course, as we were playing in a group of 9 people, you shouldn’t want to blow harder than everyone. In order to be able to listen to them all, but also to allow them to still hear themselves.

But there is more. Blowing softly is getting closer to the silence. It is listening deeper to the breath and to the connection with the group. Sometimes, I couldn’t make any sound but just continued to blow and felt still connected. A few times, I stopped blowing in the flute to release physical tensions, but stayed in the concentration of the group, and this worked beautifully too.

Playing kyotaku is all about breathing.

Letting go

The most challenging for me was to let go of intonation. When you play in a group of flutes of different lengths, the sounds make a cluster where you loose yourself. You can see it as a lesson of letting go of control and letting go of result. I could enjoy this aspect of it, but I must confess I missed the musical result, mostly because I had then no idea how the music we played was supposed to sound. I guess that in a one-to-one session, you can learn the musical side of the piece. Listening to recordings when back home, I could settle in one sound at a time and enjoy the music fully.

I really enjoyed when we played some pieces that we both have in our repertoire: Kyorei, HiFuMi Chō (although those are not from the Hijiri-kai repertoire, I do teach them) and Yamato Choshi.

And also the RO-buki. Like it also happens during our Fukiawase sessions, after a while, the individual sounds tend to blend in and stabilise in one “tone colour”. This made our Ro-Buki become a complex bourdon, on which we, at the end, one by one, improvised.

Beyond styles, instruments and ornaments, we could find one common language between the 3 shakuhachi players (2 of my students came to the workshop as well) and the 5 already experienced kyotaku players (+ 1 absolute beginner, making it 9 people), and reach together the essence of blowing.

Beyond styles, instruments and ornaments, we could find one common language between the 3 shakuhachi players (2 of my students came to the workshop as well) and the 5 already experienced kyotaku players (+ 1 absolute beginner, making it 9 people), and reach together the essence of blowing.

Who am I?

After having tried many flutes, I found out that my (Jiari) shakuhachi (especially my 1.8 and my 2.4, made by the same maker) is the flute which best allows me to discover and express myself. I also have two (European) Jinashi shakuhachi at home that I want to explore deeper (a 2.2 made by Jose Vargas and a 2.8 made by Thomas Goulpeau). Tilo’s beautiful Kyotaku are a step further in the opposite direction I am going to at the moment. Playing Kyotaku means for me making adjustments in embouchure and hands position, and changing some reflexes. But I keep the inspiration in mind.

And I still believe that “blowing zen” is a mind- body training which can be done on any instrument. The apparent technical simplicity of the music for kyotaku makes it maybe more accessible at the beginning than the elaborate ornaments and techniques in some other schools, but it is for me just a question of training and taste. Behind the complexity, there is always simplicity and pure lines. Mastery is to go beyond technical issues and find yourself.

“Kyotaku Breeze”

In 2019, Tilo released a new CD “Kyotaku Breeze“. A beautiful Kyotaku contribution to Koten Honkyoku recordings. Tilo’s warm and peaceful sound reaches the heart directly. I like the fragility and yet steadiness of high notes on long flutes and the deepness of the low tones. I am particularly touched by Reibo (which is already one of my favourite honkyoku in our repertoire). Saji remains a surprising piece, in any style, using extended technics to explore a broader range of sounds.

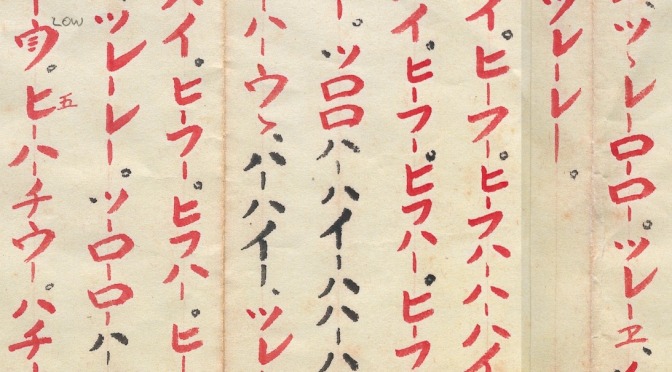

Nishimura Koku’s compositions

The rest of the weekend was devoted to study compositions by Nishimura Koku and play them during a Suizen-kai session. I didn’t attend it so I can’t write much about it. But already during the beginners workshop, we got a glimpse of Nishimura’s music, playing a couple of his compositions (Soe and Ichionjobotsu). Tilo kindly gave us recordings made by Nishimura Sensei’s son Koryu and so I could listen to them afterwards.

Update JANUARY 2021

Today I received a kind message from the Danish Kyotaku player Anders Nordin who made a recording of some compositions by Nishimura Koku. You can listen to them here.

Conclusion

It was quite a challenge to adapt to this flute, but it was definitively worth it. I enjoyed the sharing of the music, the common love for shakuhachi/kyotaku, the breathing and blowing together. And also the conversations, exchange of experiences and thoughts, and getting to know each other better. Thanks to Tilo’s kindness and serenity, and to Hans’ dedication, this afternoon will stay in my heart.

Looking forward to meet you again.

(Photos: Hans van Loon)

Thank you very much for your kind writing Helene , and it was a joy / pleasure having you with us. Also on behalf of Tilo. ♥

LikeLiked by 1 person